Splineless and Unsprung in Spring Canyon (1987)

and Accident in Moab

Updated August 10, 2007

|

|

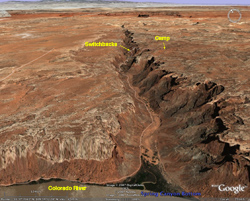

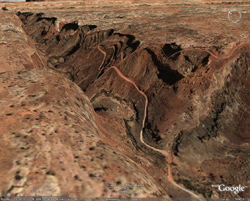

Spring Canyon is a little-visited 900-foot deep tributary off the Green RiverÕs Labyrinth Canyon, in a complex of canyons near Bowknot Bend, about a dayÕs drive from Moab on primitive 4x4 roads. The Spring Canyon Road is one of the only roads that provides access from the plateau to the bottom of the canyon, plunging into Spring Canyon at a point 2 miles north of the mouth and then continuing to the Green River. Like Labyrinth and all its other side canyons, the top half of this canyonÕs walls are vertical with a steep rubble slope below. Spring Canyon Road is easy driving on the plateau to the rim, but getting down to the bottom involves a treacherous descent along the wall on one of the steepest and roughest roads I have ever attempted in a rental jeep (one with good off-road tires, but no special equipment). Heavily eroded, the surface is rocky with large stairsteps and several switchbacks that require three point turns, and some of sections are so steep that traction in the dirt is barely sufficient to hold a jeep in place. At all times the road is hemmed in between a vertical wall and a precipice with little room to maneuver. [Note: based on trip reports, the condition of the road has dramatically improved in recent years, due to county maintenance.]

Going down, riding the brakes half of the time, is frightening, but I was most apprehensive about the return trip, as this was the only way out. We took a day trip down to the abandoned Hey Joe Mine, by the Green River at the head of Hey Joe Canyon, an 8 mile drive along the Green River from the head of Spring Canyon. Late in the afternoon on our way back from the mine, while still along the Green River, I felt my wheels spin at seemingly easy spots, in particular each time I drove up the banks of the numerous little dips and sandy washes crossing the road. The last crossing is the Spring Canyon Wash itself, just before the road starts the ascent of the wall. The wash is dry but has a sizeable sand bank on the far side, so given my troubles, I tried to pick up a little speed for this.

But speed didnÕt help, and I got bogged down with the vehicle halfway up the bank. This seemed strange, because we had no problems this morning on the opposite bank and this didnÕt look that difficult. While stopped in the sand at a sharp angle, I told my son to drive while I went outside to see what the problem was. He gave it some gas and one of the front wheels began spinning in the sand, but to my dismay, neither of the rear wheels were turning! I wasnÕt aware of any way to disengage the rear axle! Clearly, there was a serious problem: there was no way to apply power to the rear wheels, and if we couldnÕt even get up this little sand bank, there was no hope of making it out of the canyon up that 900-foot wall. Going uphill, most of a vehicleÕs weight is over the rear wheels—the front wheels contribute little to uphill traction. The steeper the slope, the less the front wheels help.

Giving up, I backed down into the level wash and jacked up the left rear corner of the jeep. With the transmission in first gear, I tried to spin the jacked-up wheel by hand. Normally the differential prevents it from rotating if the other wheel is resting on the ground, but it spun freely without resistance. It did not even seem like the wheel was connected to the differential. Was the axle severed perhaps? This was not a problem I was going to fix out here.

The obvious choice now was whether to leave this jeep down here, abandoned, and drive back in the other jeep to get a replacement jeep. But the jeep rental company was in Ouray, a long, exhausting day of driving from here (especially in these jeeps that prefer backroads to highways), so it would have put a serious damper on the rest of our vacation. Also I felt bad about leaving the Ouray people with a disabled jeep at the bottom of a canyon in another state. Our second choice was to go only as far as the nearest telephone in Moab a half day away, and call them to come out to help us in some way. That would still probably involve a day of waiting for them to come. Determined to salvage our trip, I decided to try to get this jeep out of the canyon ourselves and drive to Moab. There, maybe a mechanic could fix the problem.

We couldnÕt get up with no traction over the rear wheels, so I decided the trick to this ascent was to drive backwards! With the engine over the drive wheels trailing the vehicle, I reasoned that in reverse we would have even better traction on the ÒrearÓ axle than usual. So that a breakdown of this jeep wouldnÕt trap the good jeep in the canyon, the good jeep had to go up first. Also being in the front, the good jeep stood a chance of towing the other jeep out of any predicament.

Of course, this was a serious 4x4 road that you would never attempt without 4WD, and we had just the equivalent of 2WD. So to increase our odds, I decided I to go at a ÒhighÓ speed without stopping. Normally you would creep up about 1-2 mph, stopping frequently to scout the next obstacle. But I felt that I had run this as fast as I dared, because a stop might be my last. Still, ÒfastÓ probably meant no more than 10 mph, and of course there were the switchbacks which could not be done without reversing.

One more difficulty was that we didnÕt want the leading jeep to get very far ahead. If the rear jeep needed a tow, the front jeep would have to back down, and nothing could be more frightening than backing down this steep, tortuous road. So instead of just sending the first jeep up slowly, on its own, we had to drive up in tandem, both faster than we felt comfortable, with the rear jeep setting the pace while concentrating on maintaining speed and staying on the road, and the front jeep keeping a lookout in the rear view mirror to maintain a constant distance while negotiating obstacles ahead.

I had one small chance to test out my idea that reverse would be better than forward, by attempting to slowly get out of the wash up the sand bank. It worked easily, so with our increased confidence, the other driver started up in the good jeep (pointing forwards) while I followed behind in reverse, looking backwards with one hand on the steering wheel. My son was in the passenger seat with his head out the side letting me know how far I was from the edge.

At first, I found this fairly easy. Yes, I was going too fast for comfort, but other than being very bumpy it seemed to work well. As we ascended to approximately the mid-point of the trail, the road took some sharp turns and we had to dodge rocks, so steering backwards became a little bit of a challenge. At our speed we began bouncing and flailing around wildly as we got to the rockiest, bumpiest part of the road, while I attempted to negotiate obstacles without stopping. Suddenly, in a narrow, curvy part of the road: crash! The jeep jerked to a cold stop, surprising us both. We hadnÕt hit anything. The jeep was still in gear with the engine running, but nothing was happening—you couldnÕt even hear a spinning wheel. What disaster was this now? My son told me the bad news: on his side of the jeep, the right front wheel was dangling off the edge of the cliff!

Scared to death that we would continue to slip off the edge, I told my son to stop leaning out the window. I applied the handbrake, shut off the engine, left it in low gear, and both of us quickly escaped out my side of the jeep. We walked around to the front and saw that the jeep was resting on its bottom, the right front wheel in mid air about six inches off the side of the cliff. I immediately realized why this happened (see analysis below) but the problem at hand was how to get out of here. The other jeep might have tried to pull us with a tow rope, but on such a steep road it barely had enough traction for itself, let alone overcoming the friction to slide a jeep back off its bottom back onto the road. Plus I was terrified that even while being pulled uphill, it might simultaneously rotate further sideways, sliding off the edge and pulling the tow jeep down with it.

But we had the most incredible luck. At this point, the cliff below was not a true vertical wall, but a very steep slope. You generally could not stand the loose parts, but there were many large stable rocks poking out of it. Directly under the wheel, about a foot below, was a perfectly flat and level rock about a foot wide, well wedged into the side of the cliff. ItÕs almost like this was planned. My thought was to jack up this corner of the jeep (with the jack on the road), pile enough large rocks on top of this flat one to reach a little above the level of the road, and then lower the jeep back onto the rocks. I reasoned I could do this in a way that with just a little help from the engine, the jeep would practically roll off the rock in reverse, uphill, back onto the road.

Maybe this plan sounds a little propsterous, but in fact it worked quite well without incident. It took the four of us about a half hour, sweating profusely, to carry enough large, heavy rocks over here. The only harrowing few seconds were when it was time to move. I had to release the hand brake at the same time as letting out the clutch and goosing the engine just the right amount, without rolling forward even an inch. I couldnÕt just gun the engine or pop the clutch because I would risk hitting the opposite wall, and also I was worried that a sudden jerk would just eject the rocks out from under the wheel (a common occurrence when using a pile of rocks for traction up a hill). I needed a firm, but very gradual acceleration from a dead stop—not something easy to do with a manual transmission on a steep hill, especially in reverse! And, failure here might mean not just losing the jeep, but my life. Fortunately I had driven this jeep enough this trip that I knew exactly how much pressure to apply to the gas pedal, and I was surprised at how easy it was to roll back onto the road.

After this, we continued our breakneck reverse ascent, much more mindful of the front endÕs need to swing out on sharp turns. We got to our campsite at the top the canyon by evening, and the next morning drove both jeeps (forwards) to Moab.

After so many days in the backcountry, arriving on the crowded main street of Moab in tourist season was more confusing and intimidating than coming up out of Spring Canyon. I was driving slowly, looking for a gas station on either side that could help us with the jeep, and when I saw one on the left, I moved into the left lane for the turn. Crash! I was rear-ended as I switched lanes, by a woman in a shiny SUV that I later found out was the wife of the townÕs police chief. The left rear fender of our jeep was demolished and the body seemed creased mid-way to the front. The SUV was also rather seriously damaged. The woman said that I was driving erratically and that I didnÕt signal my lane change. I probably was weaving around a little in my lane, driving slowly looking for a gas station, but I didnÕt think she should have tried to avoid me by quickly zooming around. After the accident, my taillight bulb was smashed, so I couldnÕt just claim my turn signal was burned out.

Several police cars came, set up cones blocking that whole side of the street, and spent a long time interviewing us and taking measurements of skid marks and vehicle locations as if this were a crime scene. Coming from the Boston area, I thought this was overkill for a fender bender, but maybe this was an unusual event in Moab. I was given a ticket for an illegal lane change and not wearing a seat belt (which came to haunt me months later in Massachusetts).

After dealing with that setback for several hours, since the jeep was still quite drivable, we went into that gas station and the mechanic looked at the problem. After removing the wheel to reveal the end of the axle, the problem was obvious: the spindle on the end of the axle is cone-shaped with many parallel splines (grooves) down the length of the cone. The wheel fits onto this cone, and likewise has a cone-shaped hole in its center, with matching splines. In this way pressing the wheel onto the axle and tightening it, the wheel and the axle turned together. Unfortunately, the splines on the axle were worn down so much, you could barely make out the grooves. Instead of having grooves, the spindle was practically smooth!

Because the rear differential was non-locking, having no resistance on one wheel meant that no power was applied to the remaining one. The mechanic tried to tighten down the wheel on the axle so that it might grab what was left of the remaining splines, but this had no effect.

There was no way for the mechanic to fix this quickly, but it didnÕt matter because I didnÕt want to drive the smashed-up jeep for the rest of our trip. I called the rental company in Ouray 150 miles away, and the owner agreed to give us a replacement jeep, on the condition that we meet him half way between Ouray and Moab to exchange jeeps, each of us therefore driving 150 miles round trip. Two of us took the broken jeep and made the exchange that same day without incident, staying in a motel in Moab that night, and then returned to the backcountry for the remainder of our trip.

Analysis

Several bad things happened here.

The mechanical problem was just one of those things you canÕt anticipate or be prepared for. The jeep was not very old and in good condition (before the accident). Jeeps on 4WD roads certainly get rough treatment, but itÕs hard to imagine how this would happen just from driving. It seems more likely caused by someone replacing the wheel without sufficiently tightening the castle nut onto the axle, allowing the splines to rub against each other and wear each other down. I have no idea what repair parts or tools one would have to take to be prepared for such a problem: an extra axle?

Should I have attempted to drive up backwards like I did? I think driving up was the right choice, saving a horrendously expensive tow. Going up forwards was out of the question, and the worst consequence of going up backwards would be to fail and be forced back down. The mistake I made was not the decision to do it, but not understanding how a vehicle behaves in reverse on a twisty road. It never occurred to me that my front was flailing left and right as I so deftly (I thought) steered the back end up the hill, since I never looked down. Making backwards turns on this narrow road with not enough room for the front end to swing requires a lot of planning and skill to start the turn just at the right point, well before reaching the corner. Even if I had thought of this, IÕm not sure I had the driving skill or reflexes to implement this at the speed I was going.

It was probably a bad decision to do it so fast. In retrospect I probably could have done it much slower. If I did get stuck at a difficult spot, it would have been a simple matter to go down a bit and try it again with more speed. If I was going slow and also had thought about the front end problem, I would have been able to negotiate the road without leaving it. Maybe if I had been a more experienced off-roader I would not have felt so daunted by the steepness and roughness of the road.

As for the accident, It was certainly a bad decision to change lanes in Moab in the way I did. To this day I donÕt know if the accident was my fault. IÕm sure I signaled the turn, but I donÕt know if the bulb was burned out (the turn signal indicator being invisible in the sun, and you canÕt hear it clicking) and I donÕt remember if there was enough time between signal and turn. If I had used my arm to signal a lane change, she probably would not have passed me, but there arenÕt a lot of arms left to do this while steering, shifting and clutching. I was going very slowly at the time, but even at 5 m.p.h. it takes but a second to leave the lane.